Damien Hirst

Artist Bio

Damien Hirst is the most prominent of the Young British Artists (YBAs) that emerged in the 1990s. This group first gained notoriety when British advertising magnate and collector Charles Saatchi began buying and showing their work in his galleries. Like many of the YBAs, Hirst confronts big themes head on, including life, death, science, and religion. His mixed-media sculptures are created from a frequently controversial assortment of formaldehyde-suspended carcasses, cigarette butts, pharmaceutical packaging, and surgical instruments, often encased in glass vitrines.

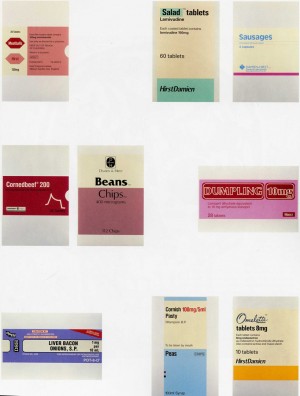

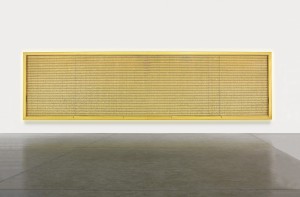

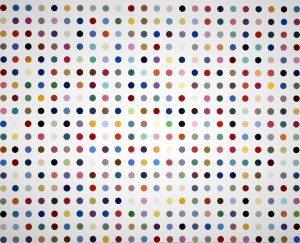

The earliest Hirst works to attract critical attention were his so-called “spot paintings,” an example of which is Chlorpropamide (pfs), 1996. The paintings are composed of hundreds of identically sized colored spots aligned into grids and named after controlled substances. In the Warholian tradition of repetitive, serial images, these unashamedly formulaic paintings use simple, cheerful means to suggest anxious questions, such as: Is art a drug? Do drugs heal or harm? Following the spot paintings, Hirst pushed further into this thematic territory by creating a series of medicine cabinets filled with drug bottles and pharmaceutical packaging, both old and new, symbolizing art’s reputed healing power.

Hirst has continued to meditate on the rituals of nature and death in often monumental, headline-grabbing scale. His most famous series, Natural History, features formaldehyde-preserved animals in large tanks, such as Away from the Flock, 1994, in which a sheep is suspended in fluid. The subject vacillates between its nascent, wooly state and its current lifeless, pickled state, referencing the sacrificial lamb as a representation of Christ. Hirst looks for an aesthetic beauty in death, often with the realization that beauty itself may depend on cycles of life and the passing away of matter.

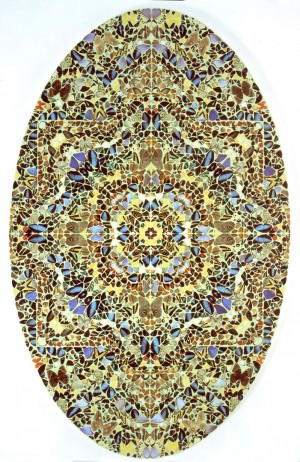

Such haunting beauty is found in The Kingdom of the Father, 2007, a colossal triptych made of thousands of butterflies mired in house paint. The deaths of the butterflies add a sobering note to the astonishing grandeur of the paintings, made to mimic the stained glass of a church apse. By turning raw, physical matter into an object of seemingly metaphysical import, Hirst upends our assumptions about how images represent reality and communicate culturally.