Urs Fischer

Artist Bio

Swiss artist Urs Fischer considers his artwork a “collision of things,” and often his collisions are large and memorable. For Untitled, 2004, he built a house in Vienna out of bread, only to watch it decompose and be eaten by birds, eventually collapsing. In You, 2007, Fischer dug through the floor of Gavin Brown’s enterprise, leaving a giant hole in the gallery that visitors could walk down into. For his 2009 New Museum exhibition, Urs Fischer: Marguerite de Ponty, the artist lowered the ceiling of museum’s third floor. Fischer’s renegade persona and ambitious output have drawn comparisons to German artists Sigmar Polke and Martin Kippenberger, who focused on the momentum of creative energy for critique, humor, and transformation.

To understand Fischer’s collisions, it is helpful to think about the fundamental character of the objects chosen to collide. For instance, in perhaps Fischer’s most famous series of sculptures, Service à la française, 2009, inkjet images of a variety of ordinary items are printed on polished stainless steel boxes. The mirrored boxes have a professional finish with sharp edges and material precision. The images, on the other hand, are of objects worn with use—brooms, phone books, cigarette lighters, chains, and even food. Lush, deep textures compete for attention with polished flatness in an unconventional take on the fabricated nature of minimalism. Fischer indulges the exactness of minimalism while at the same time allowing the irreverent world of everyday objects to intrude.

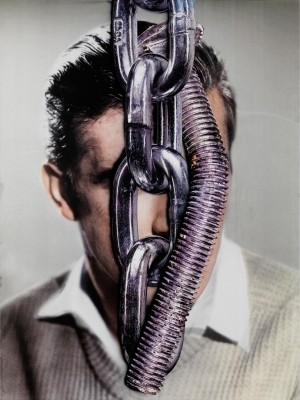

Problem Painting, 2012, shows another of Fischer’s collisions. Here, an enormous aluminum panel, almost twelve feet high, depicts a face obscured by a chain and a plastic tube; the conjunction is meant to be random, whimsical, and funny. The work is an extension of a long project of photo collages Fischer began more than a decade ago, much in the spirit of the mirrored boxes. Again, the viewer finds the gnarled, used texture of the tube and chain juxtaposed with the clean, professionally photographed headshot on the seamless, polished panel—both surface and object. Fischer builds these strange relationships, these wrecks of unlikely pairs, while winking at pop art, assemblage, and even Dada in the process. Ultimately, the off-kilter result is delightfully strange.