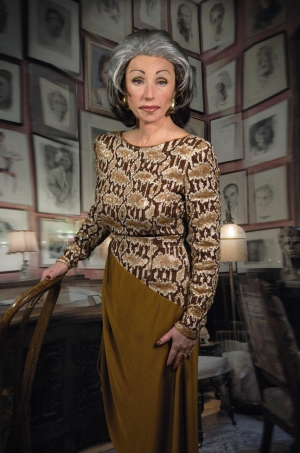

Photo by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

Cindy Sherman

Artist Bio

“I am trying to make other people recognize something of themselves rather than me.” —Cindy Sherman

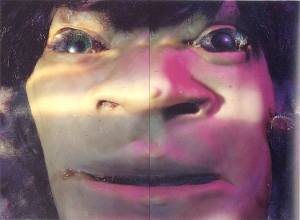

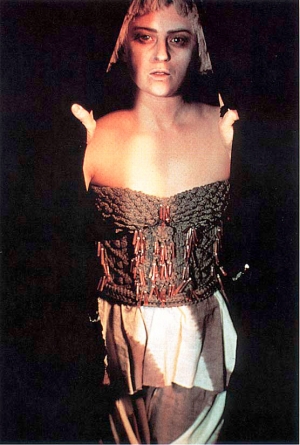

Cindy Sherman is one of the best-known and most important artists working today. Her decades-long performative practice of photographing herself under different guises has produced many of contemporary art’s most iconic and influential images. At the heart of Sherman’s work is the multitude of identity stereotypes that have arisen throughout both the history of art and the history of advertising, cinema, and media. Sherman reveals and dismantles these stereotypes as well as the mechanics of their production in creating series after series of photographs that focus on particular image-making procedures. The Broad collection has been dedicated to the work of Sherman for over thirty years and its holdings are unmatched globally.

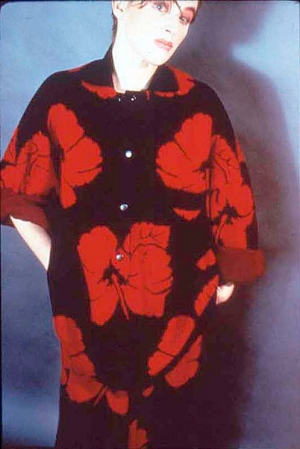

In her first works, small black-and-white photographs known as the Untitled Film Still series, Sherman explored images of women in films of the 1950s and 60s. In the film stills, rather than quoting from recognizable movies, Sherman suggests genres, resulting in characters that emerge as personality types instead of specific actresses. The first six images of the series, including Untitled Film Still #6, 1977, depict the same blonde actress at various stages of her career. Later, the character in Untitled Film Still #34, 1979, appears as a seductress, waiting at home for her lover, and in Untitled Film Still #35, 1979, Sherman might be seen as the trope of the diligent, stay-at-home wife who remains sexually attractive and available to her husband.

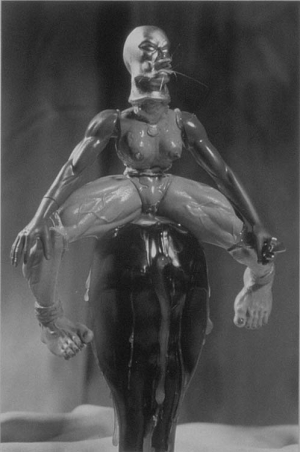

In a more recent series, featuring larger color photographs, Sherman restaged the settings of various European portrait paintings of the fifteenth through early nineteenth centuries. In Untitled #205, 1989, Sherman poses as La Fornarina, just as the model might have been painted by her lover, the sixteenth-century Italian painter Raphael, or later by Ingres. Here, however, Sherman’s Fornarina exposes milk-swollen breasts made of plastic and cradles a false pregnant belly beneath her shawl. Sherman’s obvious use of prosthetic body parts and theatrical setting compel the viewer to think about the posturing and modeling of the original historical sources. For this reason, many critics have praised Sherman’s deconstruction of overtly masculine visions of the female in the history of art.