Shirin Neshat

Artist Bio

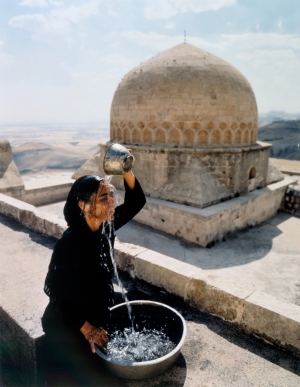

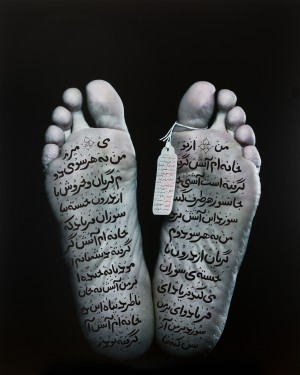

Shirin Neshat’s photographs and videos address individual freedoms under attack from or repressed by social ideologies. Throughout most of Neshat’s career, she has been exiled from Iran, an outside observer of the increasing rigors of Islamic law’s effect on the country’s women and daily life. In 1990, Neshat visited Iran after twelve years. She was shocked to find women, following the 1979 Islamic revolution, forced to wear the chador, the traditional Islamic veil. Neshat returned to the United States to make the Women of Allah, 1994, a series of self-portraits in which she wears the chador. In the photographs, her face, feet, and hands (the only parts of the body allowed to be shown by Islamic law) are covered in Iranian poetry by Forough Farrokhzad and Tahereh Saffarzadeh. The poetry, placed in sharp contrast to the uniformity of the veil, suggests a personal depth and feeling that often goes unnoticed. The women of Allah are more than icons of oppression; they are complex individuals with desires and ambitions, moving between intense private thoughts and emotions and public political involvement.

The breadth of Neshat’s work extends beyond identity politics, however. As cultural critic Eleanor Heartney observed, Neshat “makes art through her identities as an Iranian and as a woman, but reshapes them to speak to larger issues of freedom, individuality, societal oppression, the pain of exile, and the power of the erotic.” Possessed, 2001, presents a woman without chador, roaming through the streets of an Iranian city. She is overcome with madness and is completely ignored until she takes a platform. Her private suffering then becomes public, and political, attracting a crowd that debates her mania. The mass of people subsequently takes on the traits of her madness, while the woman slips away unnoticed.

Rapture, 1999, is one part of a trilogy produced by Neshat that includes the other highly acclaimed works Turbulent, 1998, and Fervor, 2000. Rapture shows a divided world where architecture and landscape stand as metaphors for entrenched cultural beliefs about men and women. The men are trapped in a fortress while the women make a long journey through the desert to the sea. While the men wrestle and pray, the women eventually board small boats to leave the land entirely. As with Possessed, Rapture’s poetic potential taps into the collective dreams, fantasies, and horrors confronting the Iranian people.