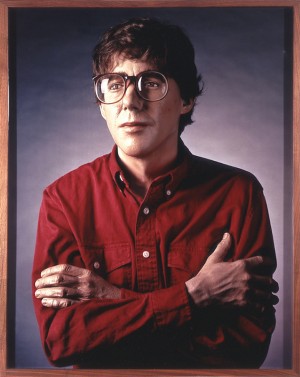

Charles Ray

Artist Bio

Small but significant alterations to familiar situations give Charles Ray’s work a disquieting tension. In NO, 1992, for example, a seemingly straightforward self-portrait is revealed to be of a mannequin designed to look like Ray rather than of the artist himself. Cloaked in simplicity, Ray’s often humorous creations comment on sculpture’s history, from its austere formal issues to its surreal psychological consequences.

Plank Piece I–II, 1973, appears directly aimed at minimalism. In the photographs, rough-grained boards are leaned against the wall, recalling both John McCracken’s brand of Los Angeles minimalism and the masculine, industrial New York minimalism of Carl Andre or Richard Serra. Also, Ray’s original frames are milled metal, in vogue for much of the 1970s, likely for its ability to speak to the work of artists such as Donald Judd. The insertion of Ray’s body into the piece puts a spin on the artist as an object, erasing the distance between the viewer and the artist. Yet, in the images, Ray is supported only by the board and wall. He does not break any rules of minimalism other than inserting himself performatively into the sculpture.

In Male Mannequin, 1990, Ray appends a super-realistic fiberglass cast of his own genitals to an ordinary store mannequin. This simple addition completely changes the meaning of the mannequin as well as the sculptural space of the gallery. Looking closely at the figure, the viewer notices that its shoulders are slumped, chest is sunken, and legs are stringy and out of proportion. The mannequin itself is an altered form of the human body, not meant to be naked but to be clothed; it is a vehicle for selling clothing. Ray unapologetically made figurative sculpture at a time when it was not popular to do so, and, in this work, he also engaged the debate over anatomically correct dolls that still periodically emerges in the media.

In an extreme manipulation of space and scale, Firetruck, 1993, is a child’s toy blown up to human proportions. The work was created for the Whitney Museum’s biennial and exhibited on Madison Avenue in front of the museum. Ray’s vision for the work, however, was compromised by this display. As curator Paul Schimmel writes, “Ray hoped that on the streets of New York the sculpture would both stick out and fit in seamlessly within the urban environment. However, surrounded by a protective barrier and police protection, Firetruck stood out like a sore thumb. It was as if the theme of childlike ambition had turned on itself to become a cruel, psychological punishment for its creator.”