Imi Knoebel

Artist Bio

From 1964 to 1971, Imi Knoebel studied under Joseph Beuys at the Kunstakademie Düsseldorf with fellow students Blinky Palermo (with whom he shared a studio), Jörg Immendorff, and Katharina Sieverding. In the wake of two world wars, decades of division, and multiple stages of collapse and renewal, these young artists necessarily aligned themselves to a history fraught with ideological conflict. Beuys was the center of this new artistic climate, retooling Germany’s romantic and lyrical past into politically and poetically charged objects, performances, and movements. Artists like Knoebel, however, felt that art should take a different path, and his work was not only different from but also often resistant to many of Beuys’s postulations and claims about the discipline.

Countering romanticism, the central tradition of German art, Knoebel revives the purity of utopian modernism, using pared down forms of constructivism to take his painting to a zero point. He attempts expression without representation or the restrictions of ideological painting programs. The goal is to purify and cleanse the present from the past and to start again, relying on new materials and aesthetic forms to move forward. Painters who came of age in the postwar era dealt with a fresh cultural memory of the ascendency and fall of German nationalism, West Germany’s rapid economic recovery and expansion after the demise of fascism, and the division and subsequent union of East and West Germany during the communist era. Knoebel’s approach was to look for the basic roots of art, which he felt were not in rhetoric but in things, in the simple interaction between humans and the essential conditions of their world.

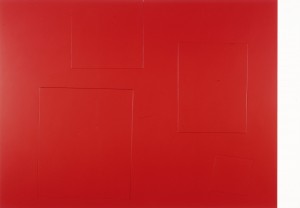

The Latinists series, 1987, clearly shows many of Knoebel’s concerns and interests. The forms, like those of American minimalism, are rudimentary (squares, rectangles, parallelograms) as are the materials of fiberboard, unused stretcher bars, and flat industrial white paint. Unlike American minimalism, however, Knoebel’s intention has nothing to do with finding a rational, positivist center by which to make art. Instead, his spare starting points become the criteria from which Knoebel’s intuitions take over, leading him to arrange his humble materials in ways that appeal to his aesthetic experiences and his perceptions of beautiful composition. The results are paintings that play into the realm of sculpture, retaining the basic figure/ground and picture plane conditions of a painting but extending off the wall and into the space, activating the room.