Photo by Timothy Greenfield-Sanders

Peter Halley

Artist Bio

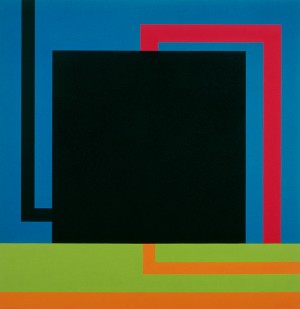

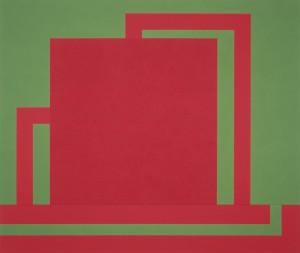

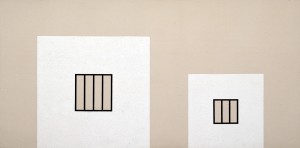

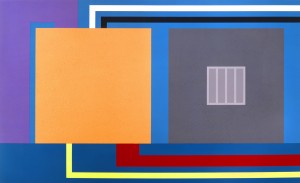

New York–based artist Peter Halley is well known for his writings on culture and art in addition to his systematic paintings. Halley’s abstractions, which he began in the late 1970s, suggest the angular and rigid geometries of structures as diverse as prison cells, computer chips, and electrical conduits. Beautiful and startling, his large, typically fluorescent images are metaphors for a “man-made” culture driven by totalizing, often stifling systems.

In many ways, Halley’s work is a direct response to and comment on the art that preceded him, and the cultural climate of the late 1970s and 80s. Many minimalists of the time, such as Donald Judd, Sol LeWitt, and Mel Bochner, used mathematical and rational systems to ground art in the objective facts of experience. Yet another group of artists rising to prominence in the 1980s, including Julian Schnabel and Enzo Cucchi, wanted a return to the art of painting as a self-expressive and subjective vehicle for meaning. Partially influenced by the theoretical writings of Robert Smithson and Michel Foucault, Halley’s work responds to both these sensibilities, presenting subjectivity as completely bound up with and regulated by systems.

Halley’s paintings convey a dual effect of urban alienation and high energy, irrevocable activity. For example, A Perfect World, 1993, is a straightforward system resembling a flowchart, but its contrasting use of muted, cool colors with hot yellows and reds gives the painting a contained pulse. Most of Halley’s work reflects this careful balance of intensities, and often the easy joys of pop culture and imagery are shown with the bleak industries and mechanisms of their creation.